It is hard to choose a chief sin of the modern Hollywood film; there are so many, the seven deadlies hardly suffice. But for me, one reigns: forgettability. How many times I have walked or subwayed down to Loews Lincoln Center only to return, two and half hours later, with only a vague sense of what intervened... The look and feel of the "down" escalator, the click of the double exit doors onto 67th (?) Street, the sense of emerging late onto a barren sidewalk (the accompanying sense that I have been "digested" by the movie theatre, processed in and processed out), the glare from the Food Emporium across the street, always meeting me there, somehow, with a reminder of stale, unwanted groceries: these sensory, homely, homemade data, repeated over years, are more vivid and lasting than almost any of the lavishly constructed images I came and paid money to see. If the reasoning is escapist, as it often is for me--why not see a movie and forget about everything for a bit?--the bargain is Faustian. It seduces you to forget life for two hours, but conceals its condition: that those two hours are lost, that you forget them too.

I saw three excellent films in the last few weeks, two of which are still, sadly, forgettable. Capote, for instance, a movie I would not dare to impugn, except, except... honestly, what did I take from it? I realized its most vivid moment for me came when Truman was reading excerpts from his book: not the scene, nothing of its filmic content, actually the prose itself, what he was reading! It was so far, in artistic quality, above any part of the film that it constituted an (unintentional, obviously) shattering indictment of film-as-art. Truman reads about the heads of the Clutter corpses concealed in cotton; we have seen this image--literally, enacted--in the film, but our glimpse of it onscreen is child's play compared to its prose rendition, chilling and magnificent. And I went also to see Good Luck, and Good Night, or however it's titled... I can't even remember the title. What I took from that viewing (again being savagely honest with myself) was mainly the opening scene, where the camera passes over faces in black-and-white, at a glamorous party, smoking and chatting, smiling in complicated ways, faces that are slightly worn, made up bravely beyond our present-day standards: a whole ethos of appearance heartbreakingly different from our own, the acceptance of wrinkles and edges and severities and strains, and all of them observed by the strangely modern camera, while wonderful Jazz Era music plays... Ahh, I thought, settling into my seat, sipping my 7-Up, this is great, but at no further point in the ensuing short film was I so satisfied. If the film had been about the substance of all of those bit characters' personal lives, about whatever they were discussing while the camera panned over them, I would have probably died of pleasure; instead it was about journalistic integrity. The transposition of Truman Capote from bleak snowswept Kansas to bleak rainswept Manhattan seemed a stage shift, not a life-shift (ah yes the noble trains criss-crossing wide, savage America), and both of these locations, even, seemed blessedly real compared to the Spanish villa where Truman and his lover get away, and eat perfectly set breakfasts against blue, cloudless Mediterranean backdrops; a drama played out in film terms, in "locations," in "scenes." So, too, the anxious newsmen fretting in the booths of CBS, the heroic frowns, the conjured banter of men with writers.

Both very good films. But in relation to the other very good film I saw in this period: fakes. Sadly--or perhaps not that sadly--this other film, Garcon Stupide, is very hard to see (playing in "alternative" venues according to an exceedingly limited schedule); and also I cannot recommend that squeamish viewers venture it, either; it is not a film for Grandma, unless she is terribly tolerant, and I'll leave it at that.

I needn't lie to myself to say it was good; I needn't force myself to remember anything; a clamorous group of images pops up in my brain, demanding attention, whenever I call the film to mind. For example, a scene where the main character goes up to the top of a mountain, to its pure overwhelmingly white snow: the film is washed out by the light, you feel that even your viewing experience is "threatened," seared away, and a surge of unexpected music merely confirms a tremendous release from the dark, indoor, night-filled, pasty, fluorescent, seedy scenes we suddenly realize we have been watching non-stop. And all he needs is that metaphor, that confluence, that departure; the filmmaker lets it go at that; there is no need to hammer in what the metaphor "means," it radiates all kinds of possible meanings in every direction; just as he merely needs to follow the glance of the 20-year-old, for a few seconds, around the little artifacts of his boyhood room to encapsulate all the traversed loss. But what is the boy feeling as he looks around? Thank God, there is no way of knowing. (Whereas in Good Night & Good Luck you always know that Murrow is stressing about the consequences of his aggressive journalism, about ideals, standards)... A conversation in the parking lot of a McDonalds; a drive-through order; cars passing through traffic circles at night; half-conversations in front of the numbing TV; Garcon Stupide is full of all kinds of authenticating, depressing realities; and yet I didn't find myself resentful at being dragged from my escape into life; I was grateful to be reminded of things I see every day: grateful to be reminded not to forget them.

Always be suspicious of people who tell you that something is "real," and something else is not. That I suppose includes me in this blogpost. I have my own agendas. I don't want to make a case for reality, however, so much as for memorability. I should add to the list of this movie's virtues that it rekindled in me an appreciation for certain aspects of Rachmaninoff (for that is what I have been told the music is)... perhaps I will finally buy that recording of Weissenberg playing Etudes-Tableaux. But Garcon Stupide has that rare asset: a director who seems to understand something about music. The concluding two minutes of the film seem musical, not by accident, but in essence. The onscreen events are reticent to declare themselves ("I am a happy ending" or "I am a sad ending," or even "I am an ending at all"?), and they take refuge therefore in the music (which cannot really declare itself either); the two enigmas are tied to each other, timed as a gradual release and disintegration, an unfolding of images and motives.

And instead of the usual spitting out down the escalator, out the corporate downward ladder, I found myself shaking, walking down the sidewalk in the Village, in no mood for bulls*** statements or any kind of interpretive crap. That means I really liked it. In this case a different bargain was made; I left with more time than I came in with; I had not sold my soul to the cinema, but instead it had sold mine back to me.

Monday, October 31, 2005

Friday, October 28, 2005

SWM, Seeking Fortune

I had just finished my tangerine peel chicken at the China Rose restaurant in Rhinecliff, New York, when three fortune cookies arrived, perched atop the check. I was waiting out a train delay. My dinner companions were accidental, or serendipitous; they have just now detrained at Poughkeepsie, and their continuing fates, other than the putative fortunes they received in Rhinecliff, will most likely be unknown to me forever.

But at that moment we were briefly together. I handed them their cookies, unwrapped mine, cracked it open, and read:

"The fortune you seek is in another cookie."

I laughed my most natural laugh, with only a dash of irony. Indeed: if only I knew in which cookie to look! How many cookies would I need to eat in order to find the fortune I seek? The question was intriguing... I loved the self-referential nature of the fortune, its void where meaning or guidance should be, its promise of an infinite, futile, sweet future. It was more a implied description of its recipient than a prediction of his future; it leaves open the possibility that my desires will always be in another cookie (my pessimistic reading), or may simply be found in some Nestle Tollhouse in February, some Petit Ecolier tomorrow.

Sometimes koans are too much for me, in their cutesy-pie profundity: just too elusive and silent to appeal to my gregarious Western mind. I like this one, though: a Mandarin fell in love with a courtesan, who told him "if you will sit outside my window for 100 days, I will then be yours." And the Mandarin placed a stool outside her window and sat for 99 days, whereupon he got up, picked up the stool again, and left. I feel this is related to the fortune I received in Rhinecliff somehow. And has wider resonances for my life these days.

My chamber group at the new Bard Conservatory just posed me a musical koan: "How do you rehearse?" I stared dumbfounded at the question. But they genuinely wanted to know. I suppose you may as well ask, "How do you speak English?" Do you have a little time? But, oddly, I had the attack of a desire to answer this question somehow ... and began talking, without any plan, and found myself interestingly circling around the topic of individual desire--rather than the more intuitive, obvious chamber music issues of listening, cooperation, sharing, interaction. It has seemed to me lately (and I think it is fair to say I play a fair amount of chamber music!) that sharpening or making more vivid what I bring to the table--purely in terms of my playing, on its own--is the most reliable way to improve a chamber music performance, and may be possibly thousands to millions of times more effective than any verbal comment I may make to my colleagues. In other words: look after your own house. I may have gotten this idea, or at least the clear expression of it, from Peter Wiley, who was (and surely still is) always asking his colleagues to play it how they want it, asking them to lead. And then, as you ineptly lead, you figure out you're actually the problem.

But as I was describing it to these coachees of mine, finding some way to verbalize my concept of an ideal rehearsal (when they probably just wanted something simpler, a flow-chart perhaps), it found its expression not so much in leadership but in the idea of communal imagination. As in, everybody imagines things about their parts, and brings these imagined concepts into the forum, and tries to make them understood to others--to express something truly imagined is difficult. The rehearsal is, therefore, not a place to smooth out differences but to let difference speak. Realizing that disagreement can be the least of a group's problems. I would say chamber music most often suffers from too much agreement. (Too "easy" an agreement, both with each other and with the music.)

Of course the imagined ways of playing things butt up against realities, impossibilities, personalities, etc. etc. Rehearsal, like practicing on one's own, is shot through with the tension of the desires/realities (cookies of tomorrow, unattainable cookies) and can only be truly productive if everyone perceives and accepts this tension. If I let myself become the obsessive practicer that lurks inside me somewhere, at some point things go awry; if I want to cross every T and dot every I, I find that new T's and I's start cropping up, making a mockery of my diligence. My dream of completion is a trap. Sometimes it is better if I leave on the 99th day... then the hundredth day of sitting somehow happens "by accident."

Well my train is hurtling down the Hudson, and I am babbling like the Dr. Phil of chamber music, arrgggghhh. I look around, and the fellow next to me catches my eye, and then feels weird about it, and then shakes his head more violently to the music pumping through his headphones, as if to say: "See, I'm really listening to music! Not staring at you!" And how could I have known this morning when I put on my socks and, not finding any matching pairs in my dresser, settled for one black and one blue--how could I have known then that I would have an insane desire to pull off my shoes in the overwarm train and put up my feet on the opposite bench of the cafe car and that my mismatchedness would then be evident to all passing Amtrak riders? This fortune must have been concealed in yet another cookie.

But at that moment we were briefly together. I handed them their cookies, unwrapped mine, cracked it open, and read:

"The fortune you seek is in another cookie."

I laughed my most natural laugh, with only a dash of irony. Indeed: if only I knew in which cookie to look! How many cookies would I need to eat in order to find the fortune I seek? The question was intriguing... I loved the self-referential nature of the fortune, its void where meaning or guidance should be, its promise of an infinite, futile, sweet future. It was more a implied description of its recipient than a prediction of his future; it leaves open the possibility that my desires will always be in another cookie (my pessimistic reading), or may simply be found in some Nestle Tollhouse in February, some Petit Ecolier tomorrow.

Sometimes koans are too much for me, in their cutesy-pie profundity: just too elusive and silent to appeal to my gregarious Western mind. I like this one, though: a Mandarin fell in love with a courtesan, who told him "if you will sit outside my window for 100 days, I will then be yours." And the Mandarin placed a stool outside her window and sat for 99 days, whereupon he got up, picked up the stool again, and left. I feel this is related to the fortune I received in Rhinecliff somehow. And has wider resonances for my life these days.

My chamber group at the new Bard Conservatory just posed me a musical koan: "How do you rehearse?" I stared dumbfounded at the question. But they genuinely wanted to know. I suppose you may as well ask, "How do you speak English?" Do you have a little time? But, oddly, I had the attack of a desire to answer this question somehow ... and began talking, without any plan, and found myself interestingly circling around the topic of individual desire--rather than the more intuitive, obvious chamber music issues of listening, cooperation, sharing, interaction. It has seemed to me lately (and I think it is fair to say I play a fair amount of chamber music!) that sharpening or making more vivid what I bring to the table--purely in terms of my playing, on its own--is the most reliable way to improve a chamber music performance, and may be possibly thousands to millions of times more effective than any verbal comment I may make to my colleagues. In other words: look after your own house. I may have gotten this idea, or at least the clear expression of it, from Peter Wiley, who was (and surely still is) always asking his colleagues to play it how they want it, asking them to lead. And then, as you ineptly lead, you figure out you're actually the problem.

But as I was describing it to these coachees of mine, finding some way to verbalize my concept of an ideal rehearsal (when they probably just wanted something simpler, a flow-chart perhaps), it found its expression not so much in leadership but in the idea of communal imagination. As in, everybody imagines things about their parts, and brings these imagined concepts into the forum, and tries to make them understood to others--to express something truly imagined is difficult. The rehearsal is, therefore, not a place to smooth out differences but to let difference speak. Realizing that disagreement can be the least of a group's problems. I would say chamber music most often suffers from too much agreement. (Too "easy" an agreement, both with each other and with the music.)

Of course the imagined ways of playing things butt up against realities, impossibilities, personalities, etc. etc. Rehearsal, like practicing on one's own, is shot through with the tension of the desires/realities (cookies of tomorrow, unattainable cookies) and can only be truly productive if everyone perceives and accepts this tension. If I let myself become the obsessive practicer that lurks inside me somewhere, at some point things go awry; if I want to cross every T and dot every I, I find that new T's and I's start cropping up, making a mockery of my diligence. My dream of completion is a trap. Sometimes it is better if I leave on the 99th day... then the hundredth day of sitting somehow happens "by accident."

Well my train is hurtling down the Hudson, and I am babbling like the Dr. Phil of chamber music, arrgggghhh. I look around, and the fellow next to me catches my eye, and then feels weird about it, and then shakes his head more violently to the music pumping through his headphones, as if to say: "See, I'm really listening to music! Not staring at you!" And how could I have known this morning when I put on my socks and, not finding any matching pairs in my dresser, settled for one black and one blue--how could I have known then that I would have an insane desire to pull off my shoes in the overwarm train and put up my feet on the opposite bench of the cafe car and that my mismatchedness would then be evident to all passing Amtrak riders? This fortune must have been concealed in yet another cookie.

Thursday, October 27, 2005

Brahms Imperfect

Today is one of those clear days when my mind is casting about, in its freedom, for something to be unhappy about. Move on, I tell it (my mind), as if jostling someone on the subway; there is no woe here; but presently relentless motion itself becomes that cause of unhappiness which my mind had sought in stationary, obsessive contemplation. Another day, another Catch-22. I know, for example, I want to choose something to do, I am the child in the candy store, but after choosing, what then? I do not want to do the thing I have chosen.

Today's earbug is the "2nd theme" from the final movement of Brahms' Clarinet Trio. It is appropriate that it plays over and over in my head, as the theme has an imperfect subjunctive quality. I await correction of my grammatical insights here, but I believe this tense (which doesn't really exist in English) refers to things which are "repetitive, ongoing, incomplete." My wonderful Musicology prof at Indiana, Leslie Kearney, gave a riveting lecture in which she discussed the prevalence of this tense in the Russian language, its relation to Russian culture and history in general, and its applicability to Russian music. Just today, wandering around the city, I found Oblomov by Goncharov prominently displayed at the Three Lives Bookstore, which was one of my prof's pieces of cultural proof. An odd coincidence: Oblomov is the comic/tragic story of an inactive man, a metaphor for Russian apathy.

This theme I am thinking of, the one from the Brahms trio, is an odd bird. It begins with four singing notes, which could be the beginning of any melody at all. Stop. Then a second, more active, idea is tried; this idea is reworked. No overall arc is yet evident. Then just the beginning of this second idea is tried: stop. Again, the beginning of the second idea: stop. As if unable to continue. Finally, on the "third second thought," the theme finds an ending, sort of. (And begins again). It is full of unquiet rests, open-ended, frustrated phraselets. Each part of it, even the ending, seems like a new beginning, like a struggle to keep singing. And though the notes change, the theme seems to keep trying to say the same thing--not one long thing, but whatever is hinted at in each fragment as it ends.

It hangs in the brain heavily; I was singing it over and over to myself on the streets of New York, and though I was on solid Manhattan ground, I felt seasick from its fragmentary heaves. My brain was woozy; I bored myself singing it; and yet I kept on. Though it seems to get somewhere, and though it seems to have the phrase structure of a "normal theme," it is definitely not normal. It is repetitive (obviously), ongoing (it constantly wants to go on, to find the next phrase), and incomplete: though the melody has a cadence and a structure, it is hard to grasp it all in the hand or mind at once; it is made up of fragments, and these fragments "contaminate" the whole.

Brahms, perhaps, had a clear day like mine? This melody is "casting about," also; in its perpetual, searching motion it finds something reflection and stasis would not. I know my mental pacings will release themselves in some future directed energies, and this makes me want to (with your permission) add to the quasi-grammatical metaphor of imperfect subjunctive the quasi-scientific metaphor of potential energy. The Brahms theme is full of potential energy (try saying that in rehearsal at Marlboro, sometime), which becomes kinetic energy in the ensuing "gypsy" passages.

It would seem, with these kinetic energies of the virtuosic, sweeping coda, that the movement finally addresses and fulfills these lurking, dangerous potential energies of the second theme. I'm not so sure. Though the coda is full of valves to release tension, do any of them finally work? When performing it, at the moment when the audience begins applauding, I find myself looking back over the last line of music, searching for something. I skip back past the last two measure of A minor chords, and also past the two measures before that (the rather conventional cadence I-IV-V-I), in other words past the releases to what must be released: a held D minor chord in the piano. This chord for me quivers with energy, and encapsulates the horrible helplessness of the pianist; how I wish I could "do something" with that chord, rather than just play it and sit there! Once I have chosen how to play it, I must live with it; sit and wish and want is what I must do. I am powerless at this moment of great musical power. I realize as I look at it (and as they applaud, and as I get up to bow with my colleagues) that the F at the top of the chord is a dissonance against the E from the beginning of the melody--with two upward sixths, E-C, A-F, Brahms takes us up this dissonant ninth--and that temporally displaced contradiction is part of what I feel: the D minor chord, though uncontradicted in its moment of existence, though standing alone, defiant, for two and a half measures, is actually in the larger scheme irreconcilable, charged with unstable energies.

As to the final, resolving measures I often feel so what? This is how the great Brahms Clarinet Trio ends--after all its inexpressible longing--with a I-IV-V-I? I long again for the defiant, impossible D minor chord. And I wonder if that is how Brahms intended me to feel.

Today's earbug is the "2nd theme" from the final movement of Brahms' Clarinet Trio. It is appropriate that it plays over and over in my head, as the theme has an imperfect subjunctive quality. I await correction of my grammatical insights here, but I believe this tense (which doesn't really exist in English) refers to things which are "repetitive, ongoing, incomplete." My wonderful Musicology prof at Indiana, Leslie Kearney, gave a riveting lecture in which she discussed the prevalence of this tense in the Russian language, its relation to Russian culture and history in general, and its applicability to Russian music. Just today, wandering around the city, I found Oblomov by Goncharov prominently displayed at the Three Lives Bookstore, which was one of my prof's pieces of cultural proof. An odd coincidence: Oblomov is the comic/tragic story of an inactive man, a metaphor for Russian apathy.

This theme I am thinking of, the one from the Brahms trio, is an odd bird. It begins with four singing notes, which could be the beginning of any melody at all. Stop. Then a second, more active, idea is tried; this idea is reworked. No overall arc is yet evident. Then just the beginning of this second idea is tried: stop. Again, the beginning of the second idea: stop. As if unable to continue. Finally, on the "third second thought," the theme finds an ending, sort of. (And begins again). It is full of unquiet rests, open-ended, frustrated phraselets. Each part of it, even the ending, seems like a new beginning, like a struggle to keep singing. And though the notes change, the theme seems to keep trying to say the same thing--not one long thing, but whatever is hinted at in each fragment as it ends.

It hangs in the brain heavily; I was singing it over and over to myself on the streets of New York, and though I was on solid Manhattan ground, I felt seasick from its fragmentary heaves. My brain was woozy; I bored myself singing it; and yet I kept on. Though it seems to get somewhere, and though it seems to have the phrase structure of a "normal theme," it is definitely not normal. It is repetitive (obviously), ongoing (it constantly wants to go on, to find the next phrase), and incomplete: though the melody has a cadence and a structure, it is hard to grasp it all in the hand or mind at once; it is made up of fragments, and these fragments "contaminate" the whole.

Brahms, perhaps, had a clear day like mine? This melody is "casting about," also; in its perpetual, searching motion it finds something reflection and stasis would not. I know my mental pacings will release themselves in some future directed energies, and this makes me want to (with your permission) add to the quasi-grammatical metaphor of imperfect subjunctive the quasi-scientific metaphor of potential energy. The Brahms theme is full of potential energy (try saying that in rehearsal at Marlboro, sometime), which becomes kinetic energy in the ensuing "gypsy" passages.

It would seem, with these kinetic energies of the virtuosic, sweeping coda, that the movement finally addresses and fulfills these lurking, dangerous potential energies of the second theme. I'm not so sure. Though the coda is full of valves to release tension, do any of them finally work? When performing it, at the moment when the audience begins applauding, I find myself looking back over the last line of music, searching for something. I skip back past the last two measure of A minor chords, and also past the two measures before that (the rather conventional cadence I-IV-V-I), in other words past the releases to what must be released: a held D minor chord in the piano. This chord for me quivers with energy, and encapsulates the horrible helplessness of the pianist; how I wish I could "do something" with that chord, rather than just play it and sit there! Once I have chosen how to play it, I must live with it; sit and wish and want is what I must do. I am powerless at this moment of great musical power. I realize as I look at it (and as they applaud, and as I get up to bow with my colleagues) that the F at the top of the chord is a dissonance against the E from the beginning of the melody--with two upward sixths, E-C, A-F, Brahms takes us up this dissonant ninth--and that temporally displaced contradiction is part of what I feel: the D minor chord, though uncontradicted in its moment of existence, though standing alone, defiant, for two and a half measures, is actually in the larger scheme irreconcilable, charged with unstable energies.

As to the final, resolving measures I often feel so what? This is how the great Brahms Clarinet Trio ends--after all its inexpressible longing--with a I-IV-V-I? I long again for the defiant, impossible D minor chord. And I wonder if that is how Brahms intended me to feel.

Monday, October 24, 2005

Regrets and Bumps

Every performance is a regret to be assuaged (and celebrated) at the next. This is not a pessimistic statement. Yesterday I was playing Beethoven's Op. 111 and had this familiar experience: just as I was playing, at that very moment, I began to realize what I really wanted to say...

What I noticed (and what it was therefore too late to express) was a specific quirk of the organization of the variations. I have often felt impatient, at chamber music coachings and lessons, when the coach insisted on dealing at length with the timing of the transitions between variations. (No, wait a little longer here. Try to end this variation "up in the air," but more finality after the next one, etc.) It always seemed to me a bit of musical "bean counting," where one focused too much on the bread and not enough on the meat of the sandwich, so to speak. But yesterday, the joints were "all up in my face." There are several very odd connections, in which Beethoven seems to deliberately introduce a disjunction at the transfer... (at the moment when you would think he would want to "smooth things over") ... just as it seems when I walk from one car to another of the Amtrak train I am in now, the connectors between cars are bumpier, wobblier, and I am more likely to spill my decaf coffee on the way back from the cafe car. Not a very transcendent metaphor.

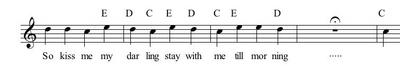

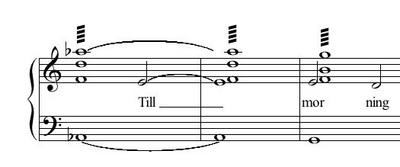

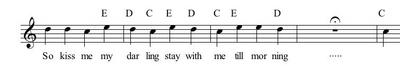

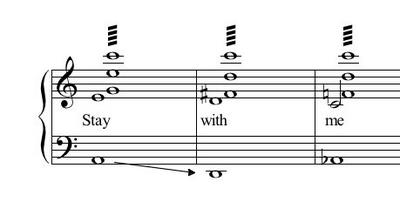

Between the first half of the theme, for instance, and the second, there is this one barren note, E. It is the only unison (unharmonized) note.

Now, I don't find the theme "sad" as a whole--its overall emotional state is wonderfully abstract--but the A minor to which this unison note leads is to my mind quite desolate. I am always struck, whether practicing, performing, or listening, at this moment: how unusual (how powerfully still) the A minor sounds, how perfectly it represents its own harmonic identity. If I am performing it, I often feel a kind of inner deflation, a call towards listening and reflection rather than playing and communication. It is deeply opposed to the raging, searching C minor of the first movement, it is not at all the same kind of minor: this A minor seems a kind of negative, exhausted mirror image--a sadness now past. These few bars of A minor are absorbed within the theme, like a bubble of minor floating in the major; each subsequent variation perpetuates this (essentially emotional) architecture, revisits the minor only to "reconvert" it to major. So, too, the moment of despair in the larger scheme of the movement, the chromatic wandering moment, the slippage, is absorbed in a larger transcendence and affirmation. I shouldn't say "despair" as Beethoven so carefully rides the line; the sadnesses in this movement are so beautiful that you cannot really get depressed about them. (Not everyone who is lost is sad.)

To return to this one unison note, E: I love it. It has its own color: dark, unmoored. It does not belong. The framework, the certainty of the previous C major is removed, but not absolutely. It is simply a pivot, the very minimum possible of transition: any more harmonic "explanation" would ruin it, would make the transition too obvious; its enigma is its meaning. Also: its short duration. It is like a vacant moment in the narrative (hollow is the word I keep coming around to in my head), a hiccup during which something is perceived.

At other junctions Beethoven introduces different kinds of hiccups. I have spent a lot of time trying to figure out how to "fit in" all the interesting voice-leading happening in the first two variations of this movement--particularly the voice-leading between halves. A lot happens. How can I give all this beautiful stuff its due, without slowing down, without losing proportion?

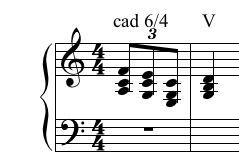

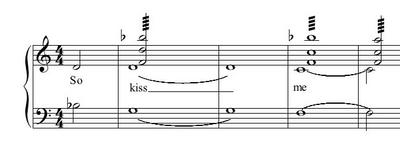

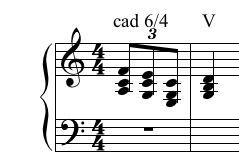

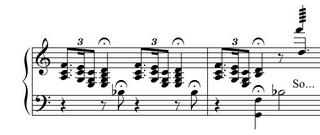

Let's take the first variation for an example. Things are going along fairly smoothly, according to a certain pattern of filling in the notes:

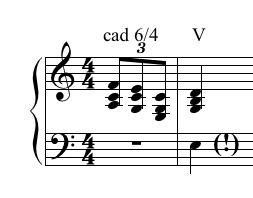

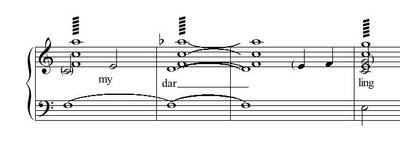

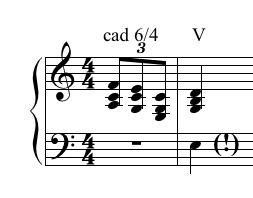

But towards the end of the first phrase the activity level jumps, the pattern is extrapolated, stretched: the chromaticism spikes. It is hard to put one's finger on it, but Beethoven introduces new, "unnecessary," complications at these cadences (A-flat, A-natural, B-flat, B-natural):

The music becomes thornier, harder to follow, a labyrinth of near-resolutions. It is as though something is building up, some excess of meaning, and Beethoven has to "cram it in" at the ends of the phrases, has to make things denser, more compressed, more fraught.

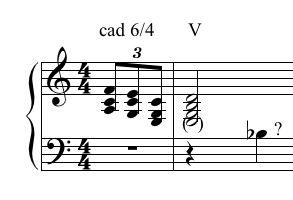

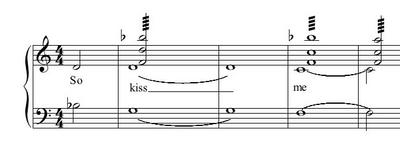

Interestingly, the transition to the A minor in the first variation is particularly fleshed out--"explained"--here a whole series of chords "stands in" for the one enigmatic E.

Precisely where the theme said the LEAST, this first variation says MOST. Beethoven is thinking end-heavy; the piece is tending towards profusion (not simplicity) in general, or at least towards an uneasy truce between profusion and simplicity, and these halves of the variations, in microcosm, tend to mirror this macrocosmic crescendo of activity.

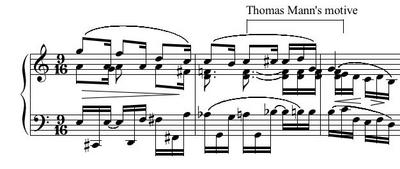

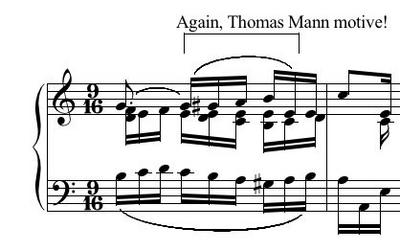

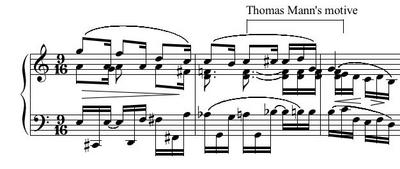

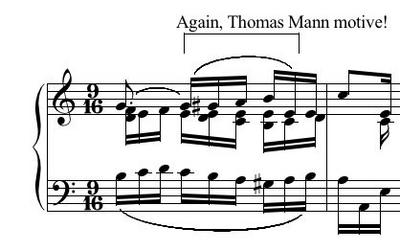

Thomas Mann, in Doctor Faustus, has a wonderful passage about Beethoven Op. 111 and he focuses on something I had hardly noticed... he concentrates on a C C# D G at the end of the movement, and the emotional importance of the introduction of the C# passing tone: which, in music theory speak, might be referred to as ... the lingering on, and complication of, the cadence.

Mann's effusion gives me some comfort, some assurance that I am not the only one out there waxing perhaps over-poetical at times... But as the musical examples above show, this C-C#-D is not a new event at the end of the piece... these little, complicated, transitions at the end of the theme halves that I have been obsessing about, these disjunct moments of crammed meaning, are intended to introduce and develop that very motive, that "most poignantly forgiving act in the world." (Did Mann make a mistake? Not look hard enough? Or did he not care?)

The "reason" why Beethoven fills out that simple E (destroys its simplicity) is to readdress this melodic idea... essentially the creation of a new mini-theme, a new object of concern, a "theme of variation." Something that happens, interestingly, only at the ENDINGS. The theme is somehow "not enough," somehow does not stand on its own... unlike in Op. 109 where the theme, in all its simplicity, proves to be plenty, and is reiterated at the piece's conclusion. Op. 111 dissolves into profusion, fragments, second thoughts.

This commentary on the theme becomes like a cameo role that steals the show. As I was playing yesterday I began to feel this second entity, its eruption at the ends of the phrases, its emergence as a competing, asymmetrical force. And I wanted to feel it much, much, more. I wanted to rewrite the piece in my head, so to speak, giving this cameo its true, central role. It was too late of course for that particular concert, but how could I regret my illumination?

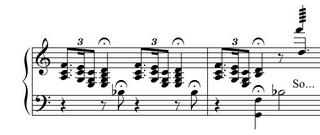

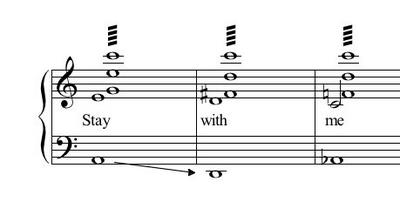

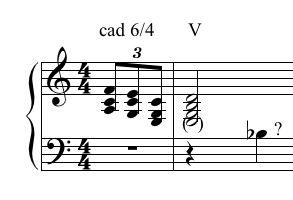

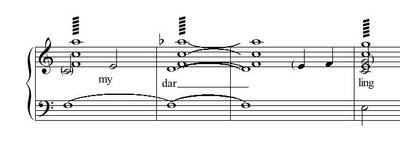

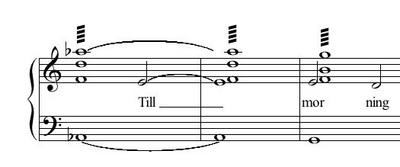

Another hiccup I found irresistible yesterday as I was playing the Sonata through was the little soft half-measure at the end of the second variation, before the forte explosion of the third ("jazzy") variation:

There it is: a tiny expression of the dominant between tonics. Beethoven insists on creating another registral space (bass-free, "inessential") for this essential chord; he makes the transition parenthetical, a non-event. (Just business.) Partly this allows the new variation to explode into being, rather than to simply occur... it complicates the transition quite a bit, like a musical "double-take," (it's loud, no it's soft, no it's loud again; it's tonic, it's dominant, no, it's tonic again!): a little flurry of activity, compressed switching of mood, register, etc... I felt yesterday as I played it that I had not yet found the right joy for that moment, the right twinkle in Beethoven's eye, and it is hard, because it goes by so quickly that, like a rural town, if you blink (or if someone in the audience coughs) you'll miss it, and yet I had the feeling as in the other transitions that it was essential, that a lot of meaning lay there in the elusive nanosecond. Many musical moments are more important than their duration would suggest.

The gradual emergence of wit from this transcendent movement is one of its most fascinating (bizarre, unexplainable) elements; yesterday as I played it, I began to feel the evil urge to let its silliness loose (sacrilege, the elephant in the china shop) but I think it lovely that Beethoven managed to sweep that aspect of the cosmos in too; the first movement has not a silly bone in its body, and the overall message of the second movement is not silly either, to say the least; but in decorating this theme, some element of the outrageous, the unassimilated, the ridiculous, creeps in and Beethoven did not, like some too-serious artists, want to let that part of existence go.

The bumps at the connections, the omission or cramming in of meaning at the ends of things; in his supreme control over materials, obviously a conscious desire not to be too smooth. "Slick" is the dangerous thing that smooth leads to; it lurks at the bottom of smooth's slippery slope. Not slick at all, this Arietta; my urge to be a "great interpreter" and sweep all the notes together in one vast arc is counteracted by Beethoven's interspersion of craggy details; and I have the feeling Beethoven wants me to continually cross-refer, from macro to micro, to constantly wonder why certain things happen, what principles they manifest, and to struggle to fit everything in, and to always feel, as I do when packing my suitcase or contemplating my schemes for life or trying to understand another person, that something, some stubborn strange something, has been left out.

What I noticed (and what it was therefore too late to express) was a specific quirk of the organization of the variations. I have often felt impatient, at chamber music coachings and lessons, when the coach insisted on dealing at length with the timing of the transitions between variations. (No, wait a little longer here. Try to end this variation "up in the air," but more finality after the next one, etc.) It always seemed to me a bit of musical "bean counting," where one focused too much on the bread and not enough on the meat of the sandwich, so to speak. But yesterday, the joints were "all up in my face." There are several very odd connections, in which Beethoven seems to deliberately introduce a disjunction at the transfer... (at the moment when you would think he would want to "smooth things over") ... just as it seems when I walk from one car to another of the Amtrak train I am in now, the connectors between cars are bumpier, wobblier, and I am more likely to spill my decaf coffee on the way back from the cafe car. Not a very transcendent metaphor.

Between the first half of the theme, for instance, and the second, there is this one barren note, E. It is the only unison (unharmonized) note.

Now, I don't find the theme "sad" as a whole--its overall emotional state is wonderfully abstract--but the A minor to which this unison note leads is to my mind quite desolate. I am always struck, whether practicing, performing, or listening, at this moment: how unusual (how powerfully still) the A minor sounds, how perfectly it represents its own harmonic identity. If I am performing it, I often feel a kind of inner deflation, a call towards listening and reflection rather than playing and communication. It is deeply opposed to the raging, searching C minor of the first movement, it is not at all the same kind of minor: this A minor seems a kind of negative, exhausted mirror image--a sadness now past. These few bars of A minor are absorbed within the theme, like a bubble of minor floating in the major; each subsequent variation perpetuates this (essentially emotional) architecture, revisits the minor only to "reconvert" it to major. So, too, the moment of despair in the larger scheme of the movement, the chromatic wandering moment, the slippage, is absorbed in a larger transcendence and affirmation. I shouldn't say "despair" as Beethoven so carefully rides the line; the sadnesses in this movement are so beautiful that you cannot really get depressed about them. (Not everyone who is lost is sad.)

To return to this one unison note, E: I love it. It has its own color: dark, unmoored. It does not belong. The framework, the certainty of the previous C major is removed, but not absolutely. It is simply a pivot, the very minimum possible of transition: any more harmonic "explanation" would ruin it, would make the transition too obvious; its enigma is its meaning. Also: its short duration. It is like a vacant moment in the narrative (hollow is the word I keep coming around to in my head), a hiccup during which something is perceived.

At other junctions Beethoven introduces different kinds of hiccups. I have spent a lot of time trying to figure out how to "fit in" all the interesting voice-leading happening in the first two variations of this movement--particularly the voice-leading between halves. A lot happens. How can I give all this beautiful stuff its due, without slowing down, without losing proportion?

Let's take the first variation for an example. Things are going along fairly smoothly, according to a certain pattern of filling in the notes:

But towards the end of the first phrase the activity level jumps, the pattern is extrapolated, stretched: the chromaticism spikes. It is hard to put one's finger on it, but Beethoven introduces new, "unnecessary," complications at these cadences (A-flat, A-natural, B-flat, B-natural):

The music becomes thornier, harder to follow, a labyrinth of near-resolutions. It is as though something is building up, some excess of meaning, and Beethoven has to "cram it in" at the ends of the phrases, has to make things denser, more compressed, more fraught.

Interestingly, the transition to the A minor in the first variation is particularly fleshed out--"explained"--here a whole series of chords "stands in" for the one enigmatic E.

Precisely where the theme said the LEAST, this first variation says MOST. Beethoven is thinking end-heavy; the piece is tending towards profusion (not simplicity) in general, or at least towards an uneasy truce between profusion and simplicity, and these halves of the variations, in microcosm, tend to mirror this macrocosmic crescendo of activity.

Thomas Mann, in Doctor Faustus, has a wonderful passage about Beethoven Op. 111 and he focuses on something I had hardly noticed... he concentrates on a C C# D G at the end of the movement, and the emotional importance of the introduction of the C# passing tone: which, in music theory speak, might be referred to as ... the lingering on, and complication of, the cadence.

But when it does end, and in the very act of ending, there comes--after all this fury, tenacity, obsessiveness, and extravagance--something fully unexpected and touching in its very mildness and kindness. After all its ordeals, the motif, this D-G-G, undergoes a gentle transformation. As it takes its farewell and becomes in and of itself a farewell... it experiences a little melodic enhancement. After an initial C, it takes on a C-sharp before the D ... and this added C-sharp is the most touching, comforting, poignantly forgiving act in the world. It is like a painfully loving caress of the hair, the cheek--a silent, deep gaze in the eyes for one last time. It blesses its object ... with overwhelming humanization...

Mann's effusion gives me some comfort, some assurance that I am not the only one out there waxing perhaps over-poetical at times... But as the musical examples above show, this C-C#-D is not a new event at the end of the piece... these little, complicated, transitions at the end of the theme halves that I have been obsessing about, these disjunct moments of crammed meaning, are intended to introduce and develop that very motive, that "most poignantly forgiving act in the world." (Did Mann make a mistake? Not look hard enough? Or did he not care?)

The "reason" why Beethoven fills out that simple E (destroys its simplicity) is to readdress this melodic idea... essentially the creation of a new mini-theme, a new object of concern, a "theme of variation." Something that happens, interestingly, only at the ENDINGS. The theme is somehow "not enough," somehow does not stand on its own... unlike in Op. 109 where the theme, in all its simplicity, proves to be plenty, and is reiterated at the piece's conclusion. Op. 111 dissolves into profusion, fragments, second thoughts.

This commentary on the theme becomes like a cameo role that steals the show. As I was playing yesterday I began to feel this second entity, its eruption at the ends of the phrases, its emergence as a competing, asymmetrical force. And I wanted to feel it much, much, more. I wanted to rewrite the piece in my head, so to speak, giving this cameo its true, central role. It was too late of course for that particular concert, but how could I regret my illumination?

Another hiccup I found irresistible yesterday as I was playing the Sonata through was the little soft half-measure at the end of the second variation, before the forte explosion of the third ("jazzy") variation:

There it is: a tiny expression of the dominant between tonics. Beethoven insists on creating another registral space (bass-free, "inessential") for this essential chord; he makes the transition parenthetical, a non-event. (Just business.) Partly this allows the new variation to explode into being, rather than to simply occur... it complicates the transition quite a bit, like a musical "double-take," (it's loud, no it's soft, no it's loud again; it's tonic, it's dominant, no, it's tonic again!): a little flurry of activity, compressed switching of mood, register, etc... I felt yesterday as I played it that I had not yet found the right joy for that moment, the right twinkle in Beethoven's eye, and it is hard, because it goes by so quickly that, like a rural town, if you blink (or if someone in the audience coughs) you'll miss it, and yet I had the feeling as in the other transitions that it was essential, that a lot of meaning lay there in the elusive nanosecond. Many musical moments are more important than their duration would suggest.

The gradual emergence of wit from this transcendent movement is one of its most fascinating (bizarre, unexplainable) elements; yesterday as I played it, I began to feel the evil urge to let its silliness loose (sacrilege, the elephant in the china shop) but I think it lovely that Beethoven managed to sweep that aspect of the cosmos in too; the first movement has not a silly bone in its body, and the overall message of the second movement is not silly either, to say the least; but in decorating this theme, some element of the outrageous, the unassimilated, the ridiculous, creeps in and Beethoven did not, like some too-serious artists, want to let that part of existence go.

The bumps at the connections, the omission or cramming in of meaning at the ends of things; in his supreme control over materials, obviously a conscious desire not to be too smooth. "Slick" is the dangerous thing that smooth leads to; it lurks at the bottom of smooth's slippery slope. Not slick at all, this Arietta; my urge to be a "great interpreter" and sweep all the notes together in one vast arc is counteracted by Beethoven's interspersion of craggy details; and I have the feeling Beethoven wants me to continually cross-refer, from macro to micro, to constantly wonder why certain things happen, what principles they manifest, and to struggle to fit everything in, and to always feel, as I do when packing my suitcase or contemplating my schemes for life or trying to understand another person, that something, some stubborn strange something, has been left out.

Friday, October 21, 2005

Shouldn't

Apparently I have underjudged the readability of my blog, as I think (though it is subject to doubt) the very person who I rather unpleasantly depicted in my last post seems to have written me a rather clever comment... and I suppose I should take into account that the target demographic of my blog would tend to include people who regularly go to Carnegie Hall (and ranges, perhaps, not far beyond). Though too little too late, I should stress the unfairness of depicting someone on the basis of a few words uttered in a concert hall (which he, if it is he, suggests to be misquoted), and my own painful eagerness to rant on occasion, and also (most importantly) the irony and hypocrisy of my ranting about disliking musicological discussions when my own doctoral document, shamefully, was entitled "Studies in Musical Continuity: Towards An Alternative View of Analysis and Form." Mea culpa. Let he who is without annoying concert-hall comments cast the first stone. Particularly I apologize for the snarky comment about "minutes immersed in music appreciation textbooks," which was a selfish, peevish gratification and little else.

However, there is a silver lining to my shame. He signed his comment "Structure Man," which gives me a whole new wonderful idea, sort of Musicology as a comic strip, with battling, macho superheroes: Structure Man vs. Moment Man!!!! How many delightful aspects of music could be covered in their battles!! More later, perhaps I will find a friend to illustrate a strip for me on Beethoven Op. 111...

My friend D. insists that I am an "unreliable narrator," (i.e. liar) in that really I'm a structure man--perhaps "wishing" I were a moment man? Perhaps I'm compensating? People often say to me after performances that my playing revealed the big structure, etc., was "all of a piece," or whatever, and I can't help wondering on these occasions if that's actually a good thing. Wait! Didn't you like the details? (Ah, the endless ingenuity of a performer's insecurities!) D. however does not dispute the likelihood of moldy dishes in my sink.

However, there is a silver lining to my shame. He signed his comment "Structure Man," which gives me a whole new wonderful idea, sort of Musicology as a comic strip, with battling, macho superheroes: Structure Man vs. Moment Man!!!! How many delightful aspects of music could be covered in their battles!! More later, perhaps I will find a friend to illustrate a strip for me on Beethoven Op. 111...

My friend D. insists that I am an "unreliable narrator," (i.e. liar) in that really I'm a structure man--perhaps "wishing" I were a moment man? Perhaps I'm compensating? People often say to me after performances that my playing revealed the big structure, etc., was "all of a piece," or whatever, and I can't help wondering on these occasions if that's actually a good thing. Wait! Didn't you like the details? (Ah, the endless ingenuity of a performer's insecurities!) D. however does not dispute the likelihood of moldy dishes in my sink.

Thursday, October 20, 2005

Molds

Happy birthday, Charles Ives! If I had a dollar for every sour look I have gotten when I have mentioned a work of Ives, or simply his name... Perhaps the Greatest Sour Look Award must go to pianist Andras Schiff, who pronounced the name with an unforgettable, Grinchian sneer which seemed to want to rob not just me, but every citizen of planet Earth, of any joys I or they might now or later find in his work. Luckily the looks always wear off. The scores themselves give much more powerful, long-lasting looks, and I look back at them, with amazement and love. And so just now, just playing the simple "Alcotts" in my living room--as a birthday tribute--I found myself touched again by something that is only a hair's-breadth away from hackneyed Americana... "common" beyond belief, deeply and embarrassingly sentimental; something that is not really at all of my experience, which dredges up an America utterly different the one I know; how can I associate with transcendentalism, hymn-tunes and marching bands, while watching Seinfeld and eating Baked Cheetos? (I don't know which is more cynical, the show or the snack.) It definitely drove home for me how much America has changed: culture's drifts and trends, our post-post-modern predicament...

Anyway.

The other night I was sitting with my friend in Carnegie Hall (that American cathedral of music), preparing to hear Richard Goode and Orpheus play a truly astonishing Beethoven C minor Concerto, when a man in the row behind me piped up. "The piece we're about to hear," he said, "is the fulfillment of the piece we heard on the first half." He was referring to Mozart's K. 271. He went on: "In the first three concertos, Beethoven stuck with the classical mold; in the last two, he broke the mold... this piece does not break the mold, it fulfills it." He was quite audible and so I was able to commence my listening experience with delicious thoughts of fulfilled mold. Need I say?--the comments were offered in a fairly tendentious tone, bespeaking minutes immersed in music appreciation textbooks. I wondered: did his companion find these comments helpful? Did she (or he, I couldn't see) listen to that menacing, dark opening tutti, attuned solely to how Beethoven conformed to the mold? Or did she/he just go with the flow, let the mood carry her? Or (option three): did she/he just sit there, unable to listen, stewing about how annoying her companion was for talking mold right before the piece was about to start?

Later that evening, at the Redeye Grill, over a Sierra Nevada, having managed to survive the whole backstage deal, I let my true feelings fly to my friend. He felt the arrogance of the tone of the speaker was the chief irritant, but I had other fish to fry. For example (Rant #1): so K. 271 needs to be fulfilled?!??!? Like that perfect, joyous masterpiece of Mozart was just sitting around, waiting for Beethoven to fulfill it, to make it bigger, badder, better? And Rant #2 had more to do with a general aversion to talk of structures, esp. "in the moment." Like whipping out an anatomy diagram before sex, for instance. Rant #3 was more sober, and analytical (ironically): I debated whether the 4th and 5th Concertos were actually less classical than #3... Though there are good arguments on either side, the Third has plenty of derring-do, plenty of foreshadowing, plenty of nineteenth-century passion; and the way Richard played the cadenza was totally electrifying, with harmonic outbursts, cries of the heart, staggering virtuosity, impetus--i.e., Romantics need look no further. The third has always been my sentimental favorite, and this performance fulfilled something in me that was not a mold at all, and my friend and I looked at each other after the first movement with wonderful smiles--elated, wowed smiles. I was breathless, and forgot I was a pianist in my pleasure. Which is hard to do. The Beethoven was so dark, angry, searching... and yet we found ourselves happy... there is always some mixture of elation in hearing a great performance, even of the saddest work.

I've been thinking about this lately, and as much as I love talk of molds and patterns and structures (and I gotta admit they matter), I'm really a moment man. That's what got me into this whole business, some beautiful short phrases, melodies, whatever, and I guess I would say that its the ability to fuse, weld, a whole bunch of amazing moments into a giant supersized moment... that is what keeps me coming back to the compositional buffet. And indeed the performance had that quality -- or, more accurately, I had that quality while the performance was ongoing -- of hanging in a moment, like in a drop of some fantastic fluid, and I was still hanging there at the Redeye, and only maybe later, after the cab dropped me off at 91st and Broadway, and after a quiet 10-second elevator ride, and some minutes staring out of my window and at the dishes in the sink (some of which were quite moldy), did the drop finally fall and splash.

Anyway.

The other night I was sitting with my friend in Carnegie Hall (that American cathedral of music), preparing to hear Richard Goode and Orpheus play a truly astonishing Beethoven C minor Concerto, when a man in the row behind me piped up. "The piece we're about to hear," he said, "is the fulfillment of the piece we heard on the first half." He was referring to Mozart's K. 271. He went on: "In the first three concertos, Beethoven stuck with the classical mold; in the last two, he broke the mold... this piece does not break the mold, it fulfills it." He was quite audible and so I was able to commence my listening experience with delicious thoughts of fulfilled mold. Need I say?--the comments were offered in a fairly tendentious tone, bespeaking minutes immersed in music appreciation textbooks. I wondered: did his companion find these comments helpful? Did she (or he, I couldn't see) listen to that menacing, dark opening tutti, attuned solely to how Beethoven conformed to the mold? Or did she/he just go with the flow, let the mood carry her? Or (option three): did she/he just sit there, unable to listen, stewing about how annoying her companion was for talking mold right before the piece was about to start?

Later that evening, at the Redeye Grill, over a Sierra Nevada, having managed to survive the whole backstage deal, I let my true feelings fly to my friend. He felt the arrogance of the tone of the speaker was the chief irritant, but I had other fish to fry. For example (Rant #1): so K. 271 needs to be fulfilled?!??!? Like that perfect, joyous masterpiece of Mozart was just sitting around, waiting for Beethoven to fulfill it, to make it bigger, badder, better? And Rant #2 had more to do with a general aversion to talk of structures, esp. "in the moment." Like whipping out an anatomy diagram before sex, for instance. Rant #3 was more sober, and analytical (ironically): I debated whether the 4th and 5th Concertos were actually less classical than #3... Though there are good arguments on either side, the Third has plenty of derring-do, plenty of foreshadowing, plenty of nineteenth-century passion; and the way Richard played the cadenza was totally electrifying, with harmonic outbursts, cries of the heart, staggering virtuosity, impetus--i.e., Romantics need look no further. The third has always been my sentimental favorite, and this performance fulfilled something in me that was not a mold at all, and my friend and I looked at each other after the first movement with wonderful smiles--elated, wowed smiles. I was breathless, and forgot I was a pianist in my pleasure. Which is hard to do. The Beethoven was so dark, angry, searching... and yet we found ourselves happy... there is always some mixture of elation in hearing a great performance, even of the saddest work.

I've been thinking about this lately, and as much as I love talk of molds and patterns and structures (and I gotta admit they matter), I'm really a moment man. That's what got me into this whole business, some beautiful short phrases, melodies, whatever, and I guess I would say that its the ability to fuse, weld, a whole bunch of amazing moments into a giant supersized moment... that is what keeps me coming back to the compositional buffet. And indeed the performance had that quality -- or, more accurately, I had that quality while the performance was ongoing -- of hanging in a moment, like in a drop of some fantastic fluid, and I was still hanging there at the Redeye, and only maybe later, after the cab dropped me off at 91st and Broadway, and after a quiet 10-second elevator ride, and some minutes staring out of my window and at the dishes in the sink (some of which were quite moldy), did the drop finally fall and splash.

Tuesday, October 18, 2005

Alumnus

As an Oberlin grad, I was touched by this mention in Slate:

I went to Oberlin and live in Manhattan, but have never been to Arianna's dining room.

As Special Prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald mulls possible charges in the Valerie Plame investigation, the gloating in liberal enclaves like Manhattan, Oberlin, and Arianna's dining room has swelled to a roar.

I went to Oberlin and live in Manhattan, but have never been to Arianna's dining room.

But seriously

What can you take seriously? This morning on Amsterdam Ave I saw a young man dressed like a catalog, in chic-prep regalia, being dragged back and forth on a leash by a small brown dog. The gravitas of his uniform was seriously undermined by this paradoxical power struggle, and other persons than me found it amusing, laughed as he passed; he was a spectacle. By his dress he seemed to take himself seriously, but life, at that moment, did not.

In assaying my various moods of the last seven days, chronicled in part on this site, my ability or desire to take things seriously has been a fascinating index. Staring out at the clouds of last week (which seem impossible on this sunny morning), I finally roused myself from the last cold dregs of a bowl of oatmeal and went to the piano, where my little spherical lamp shone especially weakly. It shone its yellowish light on the first page of Beethoven's Op. 27 #1 in E-flat major, and with no particular warm-up, after just a couple desultory arpeggiated chords, I breathed and set out through the opening bars:

Though I adore this piece, I never found its opening movement to be particularly "serious" or profound; I had viewed it, I think properly, through the lens of play. The dialogue between right and left hands seemed over-simple in the manner of a Dr. Seuss rhyme, and this simplistic quality seemed like a smile, a joke, a pleasure of Beethoven, something he wants you to share his amusement with... (grammatically dubious? I welcome suggestions from blog readers.) One might even consider the movement a bit "silly."

But in my cloudy mood, that morning, I found its silliness very serious: mirth with consequences. Perhaps I needed to take happiness more seriously? So while I had always enjoyed this music, this time it was more like a slaked thirst, as if E-flat major were a vitamin I were deficient in, and I had just swallowed a supplement. The very basic left hand scales seemed very expressive suddenly, invested with meaning as they criss-crossed from tonic to dominant, and now (you see) from this point onward this extra, more serious, meaning will be absorbed into my total concept of the piece, can never be erased or forgotten--even if I cannot ever totally recover it.

I just finished this last weekend playing the Franck Quintet for piano and strings, a piece which apparently many people have trouble taking seriously. Last season I played this work at the end of a tour in Sayville or Islip (I don't quite remember) and a man afterwards said some very unkind things about the piece, in a tone of voice I cannot forgive. This kind of dismissiveness I find very upsetting. Suddenly it seemed to me the five of us had driven out in the rain in a rental car, very tired, had nearly gotten lost in Long Island, and had worked hard in an unpleasant-sounding hall to bring the piece across, and some jerk had to mouth off... I worked myself into an inner rage about this, and came as close as I ever had to yelling at someone backstage. The Franck Quintet is, anyway, the Franck Quintet; either you "buy it" or you don't. And if you don't buy it, don't take it out on the musicians...

Perhaps I could have used the time playing the piece this weekend to indulge inner passions of my own, as indeed the Franck is awash in angst, but somehow connecting my inner moods to pieces I am playing seems to be a dangerous bet. I could take the Franck seriously, when I was practicing this weekend, as music, but when I tried to use it as therapy, I could only laugh. So: I would concentrate on simply the finger attacks, the relationships between the finger attacks, in the opening phrases; I would try to make the notes relate beautifully, and try to make the phrases not die but be longing fragments; I would think about the virtue of not doing too much ritard; I would try to get interesting, unearthly voicings in particular chords in the second movement... etc. And the deeper I delved away from "life," the closer and more seriously my attention was engaged. The piece seemed to be laughable, as reality.

Phrases ... sounds produced at the piano ... seem to be "facts," against which the contemplations of "real life" can seem like wishes or dreams. I can take a certain harmony seriously, while in life often it is hard to know what to take seriously. But then, if you don't take certain things in life seriously, can your music making really be good? I have often wondered.

In assaying my various moods of the last seven days, chronicled in part on this site, my ability or desire to take things seriously has been a fascinating index. Staring out at the clouds of last week (which seem impossible on this sunny morning), I finally roused myself from the last cold dregs of a bowl of oatmeal and went to the piano, where my little spherical lamp shone especially weakly. It shone its yellowish light on the first page of Beethoven's Op. 27 #1 in E-flat major, and with no particular warm-up, after just a couple desultory arpeggiated chords, I breathed and set out through the opening bars:

Though I adore this piece, I never found its opening movement to be particularly "serious" or profound; I had viewed it, I think properly, through the lens of play. The dialogue between right and left hands seemed over-simple in the manner of a Dr. Seuss rhyme, and this simplistic quality seemed like a smile, a joke, a pleasure of Beethoven, something he wants you to share his amusement with... (grammatically dubious? I welcome suggestions from blog readers.) One might even consider the movement a bit "silly."

But in my cloudy mood, that morning, I found its silliness very serious: mirth with consequences. Perhaps I needed to take happiness more seriously? So while I had always enjoyed this music, this time it was more like a slaked thirst, as if E-flat major were a vitamin I were deficient in, and I had just swallowed a supplement. The very basic left hand scales seemed very expressive suddenly, invested with meaning as they criss-crossed from tonic to dominant, and now (you see) from this point onward this extra, more serious, meaning will be absorbed into my total concept of the piece, can never be erased or forgotten--even if I cannot ever totally recover it.

I just finished this last weekend playing the Franck Quintet for piano and strings, a piece which apparently many people have trouble taking seriously. Last season I played this work at the end of a tour in Sayville or Islip (I don't quite remember) and a man afterwards said some very unkind things about the piece, in a tone of voice I cannot forgive. This kind of dismissiveness I find very upsetting. Suddenly it seemed to me the five of us had driven out in the rain in a rental car, very tired, had nearly gotten lost in Long Island, and had worked hard in an unpleasant-sounding hall to bring the piece across, and some jerk had to mouth off... I worked myself into an inner rage about this, and came as close as I ever had to yelling at someone backstage. The Franck Quintet is, anyway, the Franck Quintet; either you "buy it" or you don't. And if you don't buy it, don't take it out on the musicians...

Perhaps I could have used the time playing the piece this weekend to indulge inner passions of my own, as indeed the Franck is awash in angst, but somehow connecting my inner moods to pieces I am playing seems to be a dangerous bet. I could take the Franck seriously, when I was practicing this weekend, as music, but when I tried to use it as therapy, I could only laugh. So: I would concentrate on simply the finger attacks, the relationships between the finger attacks, in the opening phrases; I would try to make the notes relate beautifully, and try to make the phrases not die but be longing fragments; I would think about the virtue of not doing too much ritard; I would try to get interesting, unearthly voicings in particular chords in the second movement... etc. And the deeper I delved away from "life," the closer and more seriously my attention was engaged. The piece seemed to be laughable, as reality.

Phrases ... sounds produced at the piano ... seem to be "facts," against which the contemplations of "real life" can seem like wishes or dreams. I can take a certain harmony seriously, while in life often it is hard to know what to take seriously. But then, if you don't take certain things in life seriously, can your music making really be good? I have often wondered.

Saturday, October 15, 2005

What else? Dualities

A six-hour flight from JFK to Oakland last night proved not nearly so tedious as expected, due to a confluence of media. I had brought Joseph Campbell's book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, thinking myself sorely in need of hero-myth analysis, and meanwhile had forgotten about the saturation satellite television proffered by JetBlue.

It is hard to read one myth after another; the action goes by too quickly, is too vast and sweeping, filled with labyrinths of metaphor. And so, paragraphs of delight would be followed by long stretches where my eyes wandered over the words, searching forward, without comprehension or attachment, looking for some place to grab back on. Meaning overload.

Presently, the solution reared itself... a marathon of South Park episodes on the Comedy Channel.. and I settled into the strange routine of watching South Park and turning back to mythology only at the commercials (which I cannot abide). So there I would be, reading how

... that was one good day! ... and then I would head happily back to the story of Cartman leading a band of drunken Civil War reenactors on "invasions" of Topeka and Fort Sumter. Cartman, assuming the guise of General Lee (a juxtaposition of genius, I have to admit), writes tender letters back from the "front," expressing condolences at the loss of Kenny (inevitably, mythically), but never failing to mention, no matter the letter's recipient, "very very much I hate you, Stan and Kyle." Oops, commercial. Back to the Buddha:

All in all, time well spent. Meanwhile, Kyle is dying of a severe infected hemorrhoid; he has lost his will to live, simply because Cartman has experienced undeserved good fortune. If Cartman is happy, how can there be a God? (Another mythical question). Oddly, coincidentally, serendipitously, the writers of South Park took this opportunity to deconstruct the story of Job; they summarized its amorality deftly, cruelly, brilliantly... I was helpless with laughter... I was caught unaware in mid-sip, as God rained down ever more ruin on poor, helpless Job, and I spit up ginger ale on my book, and my aislemate glared. The connection to my now damp book of myths was peculiar, and I was reminded also that I had been taking life altogether too seriously. Compressed in a metal tube 37,000 feet up, I felt liberated; their deliberately evil humor punctured some balloon of mood that had been inflating for some time, and let my gases free. I was free to laugh about anything...

It is hard to read one myth after another; the action goes by too quickly, is too vast and sweeping, filled with labyrinths of metaphor. And so, paragraphs of delight would be followed by long stretches where my eyes wandered over the words, searching forward, without comprehension or attachment, looking for some place to grab back on. Meaning overload.

Presently, the solution reared itself... a marathon of South Park episodes on the Comedy Channel.. and I settled into the strange routine of watching South Park and turning back to mythology only at the commercials (which I cannot abide). So there I would be, reading how

... the future Buddha only moved his hand to touch the ground with his fingertips, and thus bid the goddess Earth bear witness to his right to be sitting where he was. She did so with a hundred, a thousand, a hundred thousand roars, so that the elephant of the Antagonist fell upon its knees in obeisance ... The army was immediately dispersed, and the gods of all the worlds scattered garlands.

... that was one good day! ... and then I would head happily back to the story of Cartman leading a band of drunken Civil War reenactors on "invasions" of Topeka and Fort Sumter. Cartman, assuming the guise of General Lee (a juxtaposition of genius, I have to admit), writes tender letters back from the "front," expressing condolences at the loss of Kenny (inevitably, mythically), but never failing to mention, no matter the letter's recipient, "very very much I hate you, Stan and Kyle." Oops, commercial. Back to the Buddha:

... the conqueror acquired in the first watch of the night knowledge of his previous existences, in the second watch the divine eye of omniscient vision, and in the last watch understanding of the chain of causation. He experienced perfect enlightenment at the break of day.

All in all, time well spent. Meanwhile, Kyle is dying of a severe infected hemorrhoid; he has lost his will to live, simply because Cartman has experienced undeserved good fortune. If Cartman is happy, how can there be a God? (Another mythical question). Oddly, coincidentally, serendipitously, the writers of South Park took this opportunity to deconstruct the story of Job; they summarized its amorality deftly, cruelly, brilliantly... I was helpless with laughter... I was caught unaware in mid-sip, as God rained down ever more ruin on poor, helpless Job, and I spit up ginger ale on my book, and my aislemate glared. The connection to my now damp book of myths was peculiar, and I was reminded also that I had been taking life altogether too seriously. Compressed in a metal tube 37,000 feet up, I felt liberated; their deliberately evil humor punctured some balloon of mood that had been inflating for some time, and let my gases free. I was free to laugh about anything...

The happy ending of the fairy tale, the myth, and the divine comedy of the soul, is to be read, not as a contradiction, but as a transcendence of the universal tragedy of man. The objective world remains what it was, but, because of a shift of emphasis within the subject, is beheld as though transformed.

Friday, October 14, 2005

Just cause

Last night I dreamed that I had the most wonderful idea for a blogpost, and this morning no amount of coffee can bring it back. Black, black coffee; grey clouds; the wind came along last night and blew my neatly piled mail into a total chaos, a tempest of notifications and receipts. Demons, tricksters, loosening my tenuous grip on organization. I blame the rain. How can one fight it? One dark, humid, drippy day after another.

I am posting this in revenge against the rain, partly suggested by darkness (the sunless week past), partly just because it's beautiful:

In an unrelated development, apparently we are now to seek tranquility in our dish soap:

I laughed in the aisle of the Duane Reade... The image of a tranquil dishwasher, therapized by Palmolive, smiling idiotically; smelling, scouring and scrubbing. Though the drugstore is supposedly a place one goes for health and personal care, why do I feel so often that everyone in there is up to no good? Other Manhattanites might understand my desire to re-write Dante's Purgatory, placing most of the action inside a Duane Reade; the new location on 94th Street is suggestively cavernous, looping, illogical; one has to penetrate beyond cellular service, into the bowels of the building, in order to get the simplest things (soap, paper towels); the staff seem surly guardians of a dubious salvation; I myself often feel an urge to call a friend (some temporary Virgil) to help me "get through" my visit, to explain my path back out...

You'll notice I'm in no mood to address the new Beethoven manuscript.

I am posting this in revenge against the rain, partly suggested by darkness (the sunless week past), partly just because it's beautiful:

I experience alternately two nights, one good, the other bad. To express this, I borrow a mystical distinction: estar a oscuras (to be in the dark) can occur without there being any blame to attach, since I am deprived of the light of causes and effects; estar en tinieblas (to be in the shadows: tenebrae) happens to me when I am blinded by attachment to things and the disorder which emanates from that condition.

Most often I am in the very darkness of my desire; I know not what it wants, good itself is an evil to me, everything resounds, I live between blows, my head ringing: estoy en tinieblas. But sometimes, too, it is another Night: alone, in a posture of meditation, I think about the other, as the other is; I suspend any interpretation; I enter into the night of non-meaning; desire continues to vibrate, but there is nothing I want to grasp; this is the Night of non-profit, of subtle, invisible expenditure: estoy a oscuras: I am here, sitting simply and calmly in the dark interior of love.

...

X confides: "The first time; he lit a candle in a little Italian church. He was surprised by the flame's beauty, and the action seemed less absurd. Why henceforth deprive himself of the pleasure of creating a light? So he began again, attaching to this delicate gesture (tilting the new candle toward the one already lit, gently rubbing their wicks, taking pleausre when the fire 'took,' filling his eyes with that intimate yet brilliant light) ever vaguer vows which were to include--for fear of choosing--'everything which fails in the world.'"

--Roland Barthes

In an unrelated development, apparently we are now to seek tranquility in our dish soap:

I laughed in the aisle of the Duane Reade... The image of a tranquil dishwasher, therapized by Palmolive, smiling idiotically; smelling, scouring and scrubbing. Though the drugstore is supposedly a place one goes for health and personal care, why do I feel so often that everyone in there is up to no good? Other Manhattanites might understand my desire to re-write Dante's Purgatory, placing most of the action inside a Duane Reade; the new location on 94th Street is suggestively cavernous, looping, illogical; one has to penetrate beyond cellular service, into the bowels of the building, in order to get the simplest things (soap, paper towels); the staff seem surly guardians of a dubious salvation; I myself often feel an urge to call a friend (some temporary Virgil) to help me "get through" my visit, to explain my path back out...

You'll notice I'm in no mood to address the new Beethoven manuscript.

Sunday, October 9, 2005

Puppy Love, Proven

What better morning than oatmeal, juice, coffee, whatever CDs strike my fancy, and a pile of books (Bellow, Baudelaire, Montaigne) on my bed, while the clouds gloom it up outside? And playing a phrase of Schubert over and over, for kicks, and running to the piano, trying to figure out the harmonies in Rufus Wainwright. I know these hours (the first, "most productive" hours of the day) are sinful idleness, an egghead's Eden, and only marginally my profession; I know that my own pleasure is unreasonable but it exists. Afterwards I do not feel a stomachache as I do after nachos, popcorn, etc. How can I harvest my own positive energy at these times for the world's greater good? I must be plugged in there somewhere.